A few days ago I found an online test featuring six exercises on JavaScript. For fun, wishing to challenge myself with something tricky, I decided to take it. The test proved to be very simple, so it isn’t worth a discussion. It’s what happened next that inspired this article.

I was talking with a workmate about the test and he decided to take it despite my warning about its simplicity. We compared the solutions we wrote for two of the six exercises and we found out that they were quite different: his solutions were terse and clever, mine were long and extremely simple in their approach to the problem. These differences have generated an interesting discussion that touched several topics: readability, complexity, performance, and maintainability.

Starting from the analysis of the two exercises we compared and the solutions we wrote, in this article I’ll share my thoughts about the power of simplicity in code.

But before starting the discussion, I want to describe the exercises and the solutions we came up with.

Exercise 1: the “fizz buzz” test

The first exercise is well-known as the “fizz buzz” test. This test is proposed in many interviews, regardless of the programming language(s) relevant to the position, and it’s usually given at an early stage of the interview process due to its simplicity. Nonetheless, many have found that a large number of developers can’t solve the “fizz buzz” test or even write code at all in the attempt to solve it.

The “fizz buzz” test is presented below:

Write a program that prints the numbers from 1 to 100. But for multiples of three print “fizz” instead of the number, and for the multiples of five print “buzz”. For numbers which are multiples of both three and five print “fizzbuzz”.

To keep the discussion focused, I will only report the core fizzBuzz() functions my workmate and I developed. Both of them accept a number as its only argument and return the result expected by the test.

My solution

The code I wrote for this exercise is reported below:

function fizzBuzz(n) {

var isDivisibleBy3 = n % 3 === 0;

var isDivisibleBy5 = n % 5 === 0;

if (!isDivisibleBy3 && !isDivisibleBy5) {

return n;

}

var str = '';

if (isDivisibleBy3) {

str += 'fizz';

}

if (isDivisibleBy5) {

str += 'buzz';

}

return str;

}

Other solution

The other solution for the “fizz buzz” test is the following:

function fizzBuzz(n) {

return [

!(n % 3) && 'fizz',

!(n % 3) && 'buzz'

]

.filter(Boolean)

.join('') || n;

}

Exercise 2: string formatting

The second exercise was slightly more complex than the “fizz buzz” test but still simple in its nature. The text of the exercise is the following:

Create a

strFormat()format function that accepts a variable number of arguments in input. The function behaves as follows:

- If the function is called without any argument, it returns the string “You didn’t give me any arguments.”

- If the function is called with a single argument, it returns the string “You gave me 1 argument and it is “_ARGUMENT_”.” where

_ARGUMENT_is the value of the argument provided- For all other cases the function returns the string “You gave me _ARGUMENTS-LENGTH_ arguments and they are “_ARGUMENT-1_”, “_ARGUMENT-2_” and “_ARGUMENT-N_”.” where

_ARGUMENTS-LENGTH_is the number of arguments provided, and_ARGUMENT-1_,_ARGUMENT-2_, and_ARGUMENT-N_their relevant values.So, if the call to the function is

strFormat("hello", "world", "fizz", "buzz")the string returned is

“You gave me 4 arguments and they are “hello”, “world”, “fizz” and “buzz”.”

My solution

The code that I wrote to solve this exercise is the following:

function strFormat(...args) {

if (args.length === 0) {

return "You didn't give me any arguments.";

}

if (args.length === 1) {

return `You gave me 1 argument and it is "${args[0]}"`;

}

var formattedArguments = args

.map(argument => `"${argument}"`)

.join(', ')

.replace(/(.*), (.*)$/, '$1 and $2');

return `You gave me ${args.length} arguments ` +

`and they are ${formattedArguments}.`;

}

Other solution

The solution developed by my workmate for this exercise is shown below:

function generateSentence(args) {

let n = args.length;

let sentences = [

'You didn\'t give me any arguments.',

'You gave me 1 argument and it is {lastArg}',

`You gave me ${n} arguments and they are {args} and {lastArg}`

];

let sentence = n > 1 ? sentences[2] : sentences[n];

return sentence;

}

function templateSentence(sentence, list) {

return sentence

.replace('{args}', list.slice(0, -1).join(', '))

.replace('{lastArg}', list.slice(-1));

}

function strFormat(...args) {

let list = args.map(arg => `"${arg}"`);

return templateSentence(generateSentence(list), list);

}

The power of simplicity in code

As mentioned in the introduction, the two exercises are simple and their solution doesn’t require more than a few lines of code. Nonetheless, the solutions presented in this post are really different in complexity and the approach used. I’ll start their comparison by discussing how readable the code of the two solutions is.

Code readability

My solution for the “fizz buzz” test is longer and more verbose than necessary but it gains in readability. I dare anyone having a basic knowledge of programming to not understand what the code does. But what I mean exactly with readability? Code readability doesn’t have a real definition, so every developer might explain it in a slightly different way. My definition of code readability is:

A code is readable if it can be understood by anyone with a basic knowledge of the programming language in use with a single read.

With basic knowledge of the programming language in use

I mean that the person reading the code must understand essential statements like if...else and for. This means that if a person that doesn’t meet this condition is not able to understand the code under examination, the problem is not the code.

In my definition I also mention with a single read

. If a developer has to read a code multiple times to understand what it does, the code can be improved. The less experienced is the developer that is reading the code, the better. If a piece of code can be understood by anyone in the team, the code won’t turn into a magic box that nobody touches for the fear of breaking it.

Let’s now take a closer look at my solution for the first exercise to see how it relates with such definition.

My fizzBuzz() function is made of basic language statements (if and return) and operations (modulo and assignments). In addition, the use of variable names (such as isDivisibleBy3) makes the code even easier to read.

For example, the following if statement

if (isDivisibleBy3) {

str += 'fizz';

}

is more readable than

if (n % 3 === 0) {

str += 'fizz';

}

While for most developers this change won’t make any real difference, it can have a big impact on a junior developer.

But how my function compares with the other one? The latter features the use of a couple of interesting techniques worth a mention.

The first technique relies on how Boolean expressions are evaluated in JavaScript. When a Boolean expression is evaluated in JavaScript, the rightmost value processed is returned. So, in the expression !(n % 3) && 'fizz' if n is divisible by 3, the right operand (the 'fizz' string) is evaluated and returned. This means that if n is divisible by 3, the result of the expression !(n % 3) && 'fizz' is 'fizz'. If you’re new to JavaScript this result might come as a surprise because in most languages the result of a Boolean expression is always a Boolean.

The second interesting technique employed is the use of the Boolean constructor with the filter() function. Line 6 (.filter(Boolean)) shows that the Boolean constructor is passed as the first argument to filter(). This is a method to filter all the falsy values from the array returned by the function.

Both these techniques are nice and communicate something good about the author of the code. However, this cleverness comes with a price. The price is the nontrivial cognitive effort that a less experienced developer has to put in order to be able to understand the code. Even worse, the reader of the code might not be able to understand the code at all, turning the snippet into a magic box that he or she will avoid at all costs.

Before moving to the next topic, I want to show you the shortest solution for the “fizz buzz” test:

function fizzBuzz(n) {

return (n % 3 ? '' : 'fizz') + (n % 5 ? '' : 'buzz') || n;

}

As you can see, the above fizzBuzz() function is made of a single statement. While this is a short and simple solution to the problem, what do you think of its readability?

With this question in mind, let’s discuss about code simplicity.

Code simplicity

I’ve been coding for a while now and an important lesson I’ve learned in my career is:

If there is a simpler solution to a problem, implement it.

This approach is not new and many others have come to this conclusion way before me. The above quote is nothing but a paraphrase of the KISS principle with which you may be familiar with.

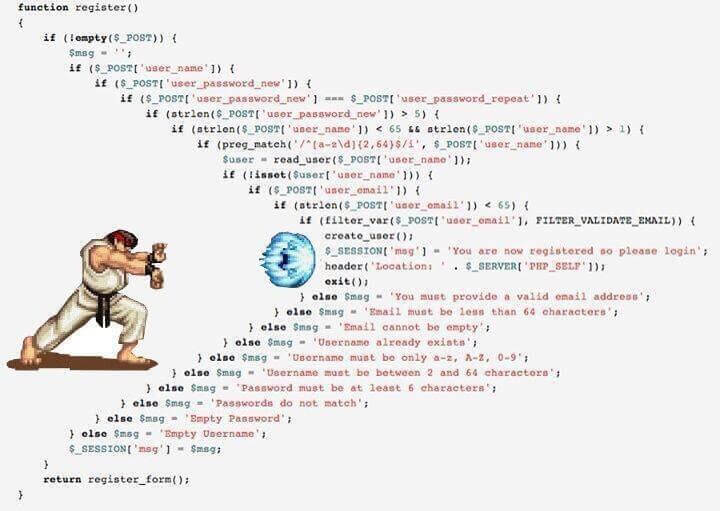

Once completed a feature, many developers tend to refactor their code to improve it. However, many of them strive for the wrong goal. Instead of refactoring to improve code readability and to implement a simpler solution, many developers focus on shortening their code, often by employing clever techniques or relying on obscure language features. A good example of this habit can be spot by looking at the second solution for the “fizz buzz” test.

When refactoring we should always strive for code simplicity. This involves reducing the cognitive effort required to understand a code. The solutions proposed to solve the second exercise offer a great starting point to analyze this aspect. This time, instead of focusing my attention on the specific lines of code written, I want to focus on the approach adopted.

My solution consists of a single function, while the other is split in three. Generally speaking, I’m all for splitting a problem into multiple, smaller problems, solve them, and then combine the solutions to solve the original problem. However, experience has taught me that going too far with this approach can be harmful.

Jumping from a function to another to grasp the aim of a code causes a lot of context switching in a developer’s brain. Too much context switching can lead to focus loss. It can also cause the loss of the original reason that firstly led to the code investigation. How many times have you started exploring a snippet of code to fix a bug and have found yourself few minutes later wondering what was your original goal? How many times have you felt that you’ve gone so many levels deep into the code that you lost track of what you were doing? I bet a lot. In these cases, it can be beneficial to combine two or more functions together to avoid too many jumps.

In conclusion, if you reach a point where a problem has become fairly simple, don’t split it into subproblems. The context switching required by those reading the code might cause them a lot of frustration. Be sure you don’t violate the single responsibility principle by combining unrelated functions, but avoid creating trivial functions.

There is yet another benefit that code simplicity can bring to the table. Let’s examine it.

A note on performance

Readability is a crucial factor when writing code, but there is another important aspect developers should be concerned about: performance. Many think that a shorter, clever code always leads to better performance. In several cases this assumption is false, in others cases the improvement in performance is irrelevant (more on this in a moment), and only in few cases it really matters. As Kyle Simpson has pointed out in several occasions, ECMAScript engines become better and better every month, and their ability to optimize code is constantly improving. So, there are cases where a developer can write terse and cryptic code that takes advantage of optimization techniques that lead to better performance compared to other solutions. But this gain will eventually vanish in a future release of the engines. Therefore, all that’s left is obscure code that nobody wants to read or change.

As an example of a clever code that doesn’t lead to a faster execution, let’s take into account the solutions for the “fizz buzz” test. My solution is more verbose and adopts a simple approach, but it’s also incredibly faster than the other. The actual difference increases with the amount of times the performance test is run. The other solution is 4x to more than 50x slower than mine. If you want to test the difference by yourself, have a look at the JSBin I’ve set up.

Comparing the solutions for the second exercise provides similar conclusions. This time the difference in performance is smaller but still relevant. The clever solution is ~2x slower than the simple one. If you want to test the difference by yourself, have a look at the JSBin I’ve set up for the second exercise.

Conclusions

In this article I’ve proposed two JavaScript exercises and the relevant solutions I and a workmate of mine have developed to solve them. These solutions are very different in their approach to the problems and have different levels of complexity, readability, and performance.

While comparing the solutions reported in this blog post, I highlighted some important lessons every developer should keep in mind. When developing and refactoring code we should always strive for code simplicity and readability, so that we reduce the cognitive effort required to understand our code. This attitude will allow anyone in our team to contribute to the code and it will avoid situations where a part of the software turns into a magic box that nobody is willing to change. A code that is simple and readable can be easily patched, extended, and changed.

The approach I’m proposing for writing code doesn’t want to limit developers’ expressiveness to a bunch of trivial features. My goal is to let developers focus more on code readability than the number of lines or the use of clever techniques. This is even more true if degradation in performance is the price to pay.